RED DRESSES

AND A NEW ROAD

BY HOLGER HOFFMANN & SYLVIA FURRER

There could not be a greater contrast between the bright red clothing worn by Kyrgyz nomadic women and their harsh everyday lives. For a long time, they lived in isolation on the high plateau at Lake Chaqmaqtin in the farthest tip of Afghanistan. Now a dirt road leads to them. This does not necessarily make their lives easier.

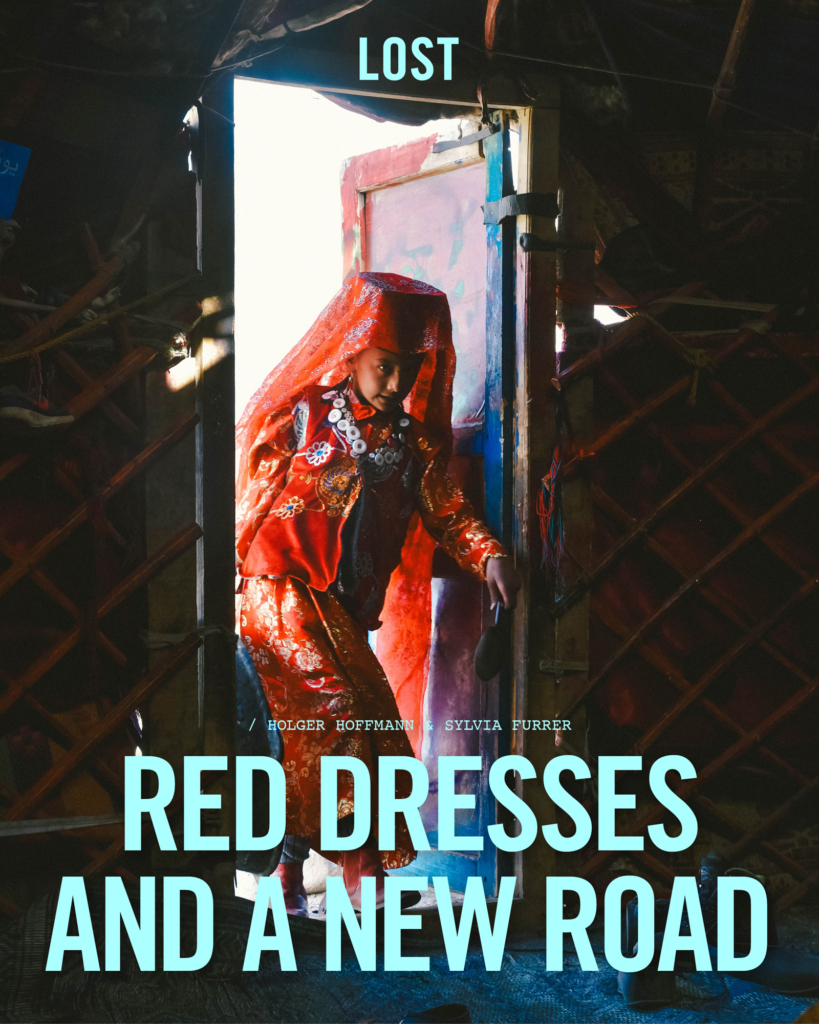

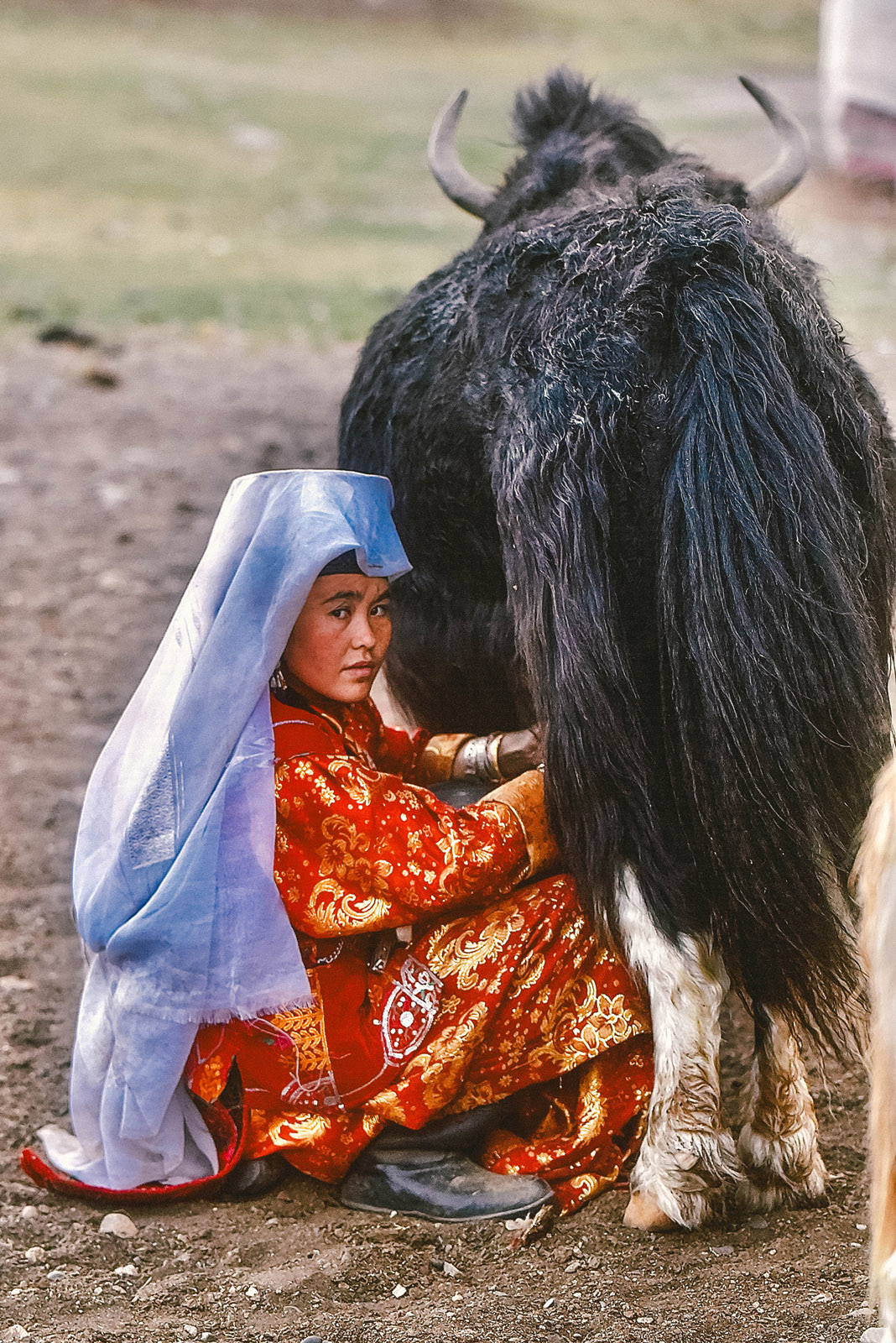

Red is the first thing that comes to mind when I think of the Kyrgyz nomads in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor. Red is the color of Kyrgyz women. Red are their ankle-length dresses printed with ornaments. Red are their vests, embroidered with buttons and adorned with all kinds of jewelry. Red are the flowing headscarves of their unmarried daughters, which they wear over cylindrical hoods. Upon marriage, however, the headscarves turn white. Men wear just the tubeteika, a round cap embroidered with colorful patterns, and a light brown chapan (traditional coat) to protect them from the cold. Red is also the dominant color inside the yurts: carpets, folded blankets, pillows, clothing chests, wall hangings, and ceiling coverings—almost everything is red.

Our enthusiasm for this unique culture was sparked by Matthieu & Mareile Paley’s stunning 2012 photo book “Pamir”. Our fascination with nomads has taken us to various tribes in Siberia, Asia, and Africa over the last twenty years, but Afghanistan seemed too risky to us during all those years. With the Taliban’s renewed takeover in 2021, calm and stability returned to Afghanistan, making the country accessible to tourists again. A year earlier, the road in the Wakhan Corridor to Lake Chaqmaqtin was completed. Until then, it took four days on foot from Sarhad e Brohil, the last village in Wakhan, to reach the Kyrgyz on the high plateau at over 4000 meters. Now it is only a day’s journey. If the rivers do not overflow their banks too much, the track is more comfortable to drive on in a 4WD vehicle than most roads in Afghanistan. But even with the new road, it takes 5-6 days from Kabul, permits from three different government agencies, and patience with the thorough but to us always correct Taliban checkpoints.

The Kyrgyz camp is sheltered from the wind at the foot of a hill, right next to a rushing stream. It consists of three simple stone houses, five yurts, with two guest tents at the edge. Eimatambeg, the clan chief, assigns us one. We are not allowed to pitch our own tent; the nomads want to make sure that they also benefit from our visit. We quickly realize that taking photos is not free either. Holger agrees with Eimatambeg on 1,000 afghani ( about USD 15) for each of the four families. But even then, the women are reluctant to be photographed. Eimatambeg explains that things used to be different.

The mood relaxes when we ask Eimatambeg to slaughter a goat for us. This brings in more cash. For the Kyrgyz nomads, a sheep is still the basic unit of their currency: a cell phone costs one sheep. A yak costs about 10 sheep and a good horse 50. The going price for a bride is 100. With the completion of the road, however, cash is becoming more and more important. They need it for gasoline for their motorcycles, for the rare cars and to pay for the goods that traders from lower Wakhan offer in their delivery trucks several times a week. Right now – it’s mid-September – apples are in demand.

While Eimatambeg is still busy gutting and cutting up the slaughtered animal, the sun sends its last rays over the hill and the animals return from the pasture: first the yak calves from the south, then the adult yaks cross the stream from the east, and finally the sheep and goats come down the hill from the west. The calves are tied up in rows and the goats and sheep are herded into a stone pen. Then the women begin milking the yaks, bringing the calves to their mothers one by one, letting them drink briefly and then milking a few liters. In the morning, before the animals go back out to pasture, the process is repeated.

In the yurt, the women boil the milk and then process it into butter, yogurt, and “kurut,” a rock-hard dry curd cheese. They fill sheep stomachs with the butter, which keeps it fresh for months. Kurut is especially popular in winter when the animals do not give milk. The women have little time to chat with each other. They are constantly busy looking after the children, feeding the animals, cooking, fetching water from the stream, washing and sewing clothes, or collecting dung and stacking it up to dry. The girls are involved in these tasks from an early age; only the youngest ones we can see playing. One of the houses in the camp serves as a school for children from all the surrounding camps. There are currently 25 children, explains the young teacher from Kunduz. But only six came today.

We ask Eimatambeg how many Kyrgyz people live here on the plateau around Lake Chaqmaqtin. He doesn’t know exactly, but he estimates around a thousand. The fact that so many Kyrgyz people live far from their homeland, isolated in this inhospitable environment, where the temperature falls below freezing 340 days a year, the wind blows across the plain and even grass struggles to grow, has its origins in the 18th century. At that time, the Kyrgyz began to use the valleys of the “Little Pamir” as summer pastureland. When winter came, they moved to warmer areas. During the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Wakhan Corridor was a refuge for the Kyrgyz. With the establishment of the Soviet Union, the borders remained closed until 1950. The Kyrgyz people thus “automatically became Afghan citizens” and could only migrate with their herds within the Wakhan Corridor. When the communist government of Afghanistan was established in 1978, some fled to Pakistan, with some of them returning soon afterwards or settling in eastern Turkey.

The new road has brought not only improvements, but also new risks and suffering. In the absence of any medical care, opium had long been the only potent medicine available to them. As a result, opium addiction was widespread among the Kyrgyz. The opening of the road has done little to improve the situation. The nearest hospital in Faizabad is four days away, too far for any emergency. And cell phones don’t work up here. As a result, the Kyrgyz have one of the highest mortality rates in the world. Women and young children are particularly affected.

Holger, as a doctor, is called to treat two men who had both had accidents on their motorcycles months ago. One had suffered a metatarsal fracture. The doctors in Faizabad had recommended surgical fixation, but this was too expensive for the nomad. Back in the Wakhan, he put weight on his foot too soon and now suffers from painful pseudarthrosis. The other, a still young man, suffered whiplash—the CT scan in Faizabad showed no injuries—and has been lying in bed severely depressed ever since.

In the afternoon, the men – young and old – begin playing “Ordo” in front of the yurts. Ordo is a traditional Kyrgyz knucklebone game that symbolizes the battle to conquer the Khan’s headquarters. Using a large yak bone, the players try to knock six smaller sheep bones – the last one being the Khan bone – out of a four-meter circle. This is the time for the women to meet undisturbed in one of the yurts for a chat. The atmosphere in the camp is relaxed again.

We want to visit more camps. The nearest one is an hours drive. On the way, we encounter five nomads migrating with their animals on the vast, otherwise very lonely plateau. Four of them are traveling on horseback with the yaks. The yurt and household goods are distributed among six yaks. The fifth nomad is following on foot with the sheep and goats. The second camp consists of only two houses and two yurts. We have brought the nomads flour, salt, sugar, apples, and honey. This does not make the reception any friendlier. Our driver advises against continuing on toward the lake. The terrain is becoming increasingly swampy. In addition, Holger is having more and more trouble with the altitude. His face is already completely swollen. Developing pulmonary edema here, like the Australian whom Holger had sent back to Sarhad e Brohil two days earlier, seems too risky to us. Sadly, we start our return journey. Sad because the living conditions up here are so incredibly harsh and sad because we didn’t have enough time to immerse ourselves more deeply in the culture of this admirable people.

SYLVIA FURRER, a Swiss lawyer/economist, and psychiatrist HOLGER HOFFMANN have traveled to over 100 countries since 1977. They became more and more fascinated by the customs and the daily life of indigenous peoples who preserve their traditional culture and subsist in remote areas under harsh conditions – from Siberia to the Danakil Desert, from the jungles of Western New Guinea to the Himalayas.

www.chaostours.ch